Understanding and improving soil using simple tools that allow everyone to assess it’s health

The life-supporting capacity of soil depends on several variables, including chemical, physical, and biological factors. For optimal soil health, the challenge lies in creating the right balance of soil structure, nutrient availability, and organic matter to build and maintain resilient, productive growing systems.

It is not always easy to measure these without sending samples away to a lab for testing or getting third-party advice. Understanding the fundamentals of good soil health is soil scientist Dr Sally Price’s specialty.

Dr Sally Price with a soil sample at Lincoln University’s Field Research Centre

Dr Price, supported by funding from the Ellett Trust, is currently soil sampling at Lincoln University’s Field Research Centre as part of the long-term Regenerative Agriculture Dryland Experiment (RADE) run by Prof Moot and Dr Alistair Black. Her research work is part of a trial to understand how to improve soil using simple tools that allow everyone to assess its health.

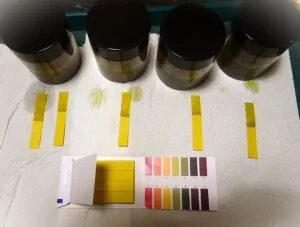

These tools include earthworm counts, pH testing, the tea bag test and nutrient analysis.

Dr Price highlighted one of the key ingredients in good soil is earthworms. “We’re trying to get aeration into the soil, we’re trying to get water movement, we’re trying to get all that good stuff happening for the roots and plants to grow and make enough feed for the sheep – worms help with this.”

“We’re looking for an average of 16 worms per spade on a sample 20cm x 20cm with a depth of 30cm. The worms like to congregate under legumes such as lucerne and clover, grab the nitrogen and then they act like little transport mechanisms to transport nutrients around the plot.”

“The lab work shows the worms are dependent on the pH of the soil, and they like a more alkaline (between 6 and 7) than acid soil. So, we’ve have been testing the pH of the soil and comparing the laneway soil samples to the paddock soil samples. The pH can tell a story about how many worms there are as a result of calcium levels and the nutrient profile.”

The third test involves burying teabags. The time it takes for a buried teabag to decompose can serve as an indicator of soil health—the faster it breaks down, the healthier the soil is. However, this process is influenced by soil temperature; during cooler months, soil organisms are less active, so organic matter decomposes more slowly.

These trials are being undertaken on low and high-fertility regenerative and dryland conventional soils. These soils are sown with a mixture of species. Dr Price acknowledges: “Soil health is not the same in any given place, so it is vital that land managers have readily available techniques that they can apply. It is about knowing the soils in your farm and how they respond to use.”

Dr Price says for any soil health test to be truly useful, it must:

Be easy to access and use regularly

Cover the soil’s biological, chemical, and physical properties

Provide meaningful, quantifiable results where possible

Be grounded in established science, even if the method is observational

“My vision is to compare user-friendly measures of soil health in regenerative and conventional agriculture under low and high soil fertility. These measures could then be used on farm for day-to-day monitoring and in other settings such as community gardens, such that tangible measures of improvements in the condition of the soil can be readily observed (and positive feedback can be readily given) by the user.”

Another aspect of the research involves community engagement or citizen science and has included participation and workshopping in local initiatives such as the Envirotown mini bio blitz and Kidsfest.

These demonstrations are a precursor to further workshops in community gardens and talks to farmers further down the track. Ultimately, these tools should give gardeners and land managers confidence that they can monitor and maintain soil health in real time. Having healthier soils and people with knowledge about how to maintain them will ultimately enhance environmental sustainability, allowing productive land to remain that way for generations to come.

Dr Price would like to acknowledge Prof Derrick Moot and Dr Alistair Black for access to the Regenerative Agriculture Dryland Experiment (RADE) trial at Lincoln University to undertake the soil health work. Also Lincoln Envirotown for giving her the opportunity to do the demonstrations at the Bioblitz, and Kidsfest. Dr Price would also like to acknowledge Prof Jon Hickford, Lincoln University for his ongoing support.